Why I am a Better Vegan Than You, Even Though I Still Eat Meat

The efficacy of veganism and offsetting

I am sorry to bait your interest with the title; I hope you are not too outraged to read the rest. Of course, I cannot be a better vegan than you, because I am not a vegan. Though I am an omnivore, I donate semi-regularly to animal welfare charities. I hypothesize that my dollars had enough positive impact to balance out the harm of every animal product I consumed this year. In this essay, I define harm broadly as animal suffering and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

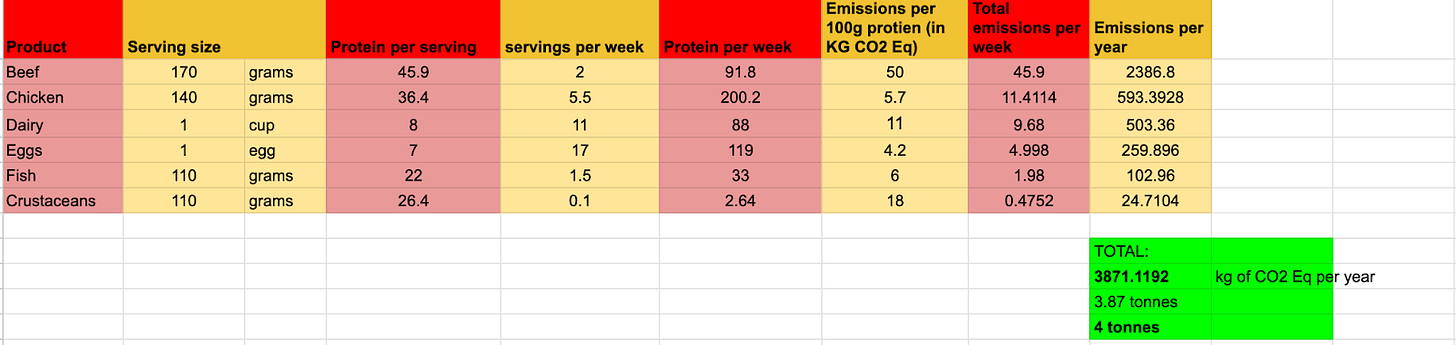

I estimate my animal consumption footprint to have been 24 chickens, 0.1 cows, 25 fish, and 71 shrimp in the past year. My consumption induced the equivalent of approximately 4 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions.

Through my $305 donation to animal welfare charities and a $150 donation to carbon offsets, I have helped remove 4.67 tonnes of CO₂ equivalents and reduced net suffering by 1917 chicken years.

Checkmate, vegans

I. On Veganism, animal suffering, and environmental impacts

Veganism is good. More precisely, factory farming and its associated animal cruelty are reprehensible. Insofar as vegans and vegetarians are contributing to reduced animal suffering, they are heroes.

Skip this part, it may sadden you:

Bear with my pathos for a moment: animals are treated horrifically. 100 billion animals on Earth are killed for meat or other products each year. 74% of all land animals are factory-farmed; in the US, this number jumps to 99%.

Factory farming is a heinous display of economy. It is significantly more efficient to pack animals in tight spaces, with little natural light or stimuli, disregarding their feelings. Chickens, for example, are confined to such claustrophobic, stressful environments that they often peck at and mutilate one another. To prevent this, they must be regularly “debeaked.”

In factory farms, close contact, poor ventilation, and stress lead to disease. The UN cites “the intensification of agriculture, and in particular of domestic livestock farming” as the primary risk driver for pandemics. Antibiotics are frequently overused, leading to antibiotic resistance. Suffering, sickness, and slaughter. These conditions are far from the idyllic view of hunting, gathering, and living harmoniously with nature.

I wouldn't willingly hurt a dog, nor a horse, nor a cow. I assume you wouldn’t either. This aversion to hurting another creature reveals our natural sympathetic response. The disturbing condition in which most animals are raised is wrong, and equally worthy of our sympathy.

(An aside on why (I believe) animal suffering matters more than environmental effects:

Firstly, the link between animal consumption and suffering is far more certain than the link between animal suffering and negative environmental effects. The path from cow flatulence to a tropical cyclone is long and arduous. Climate change is overdetermined—there are too many causes to confidently isolate and blame one. Even if we slashed the environmental impact of livestock, we are still likely to cross the 1.5 and 2.0 Celcius thresholds. Conversely, animal suffering is easily determined. The local factory farm is directly causing the suffering.

But, uncertainty is lame. Even assuming an equally direct causal link, climate change is not that bad. Er. I mean climate change is not as bad as animal suffering. Over the years, mortality rates from natural disasters have drastically decreased as wealth and preparedness have increased. This fact aside, consider that the top 25 worst natural disasters this century have killed, using the most liberal estimates, 1.034 million people. We can very safely estimate that from 2000 to 2024, 1.3 trillion animals were slaughtered. 1 trillion of those were likely factory-farmed, likely facing more cumulative suffering throughout their lives than the victims of a natural disaster.

Everyone, pull out your moral calculators! Even if we value one human life as equal to the suffering and deaths of one million animals, the climate effects still do not match the animal suffering effects. Yes, these numbers don't account for future disasters, droughts, and famines—nor the impact of climate change on wild animals. However, the disparity between the two harms remains clear.

And frankly, I care about my dog, Zeus, more than most humans.)

The sadness is over

Of course, there is an additional environmental impact as well. In 2013, livestock contributed to 14.5% of global emissions. 20% of that figure, or 2.9% in absolute terms, is associated with fuel used in the supply chain. So, subtracting the fossil fuels in disguise, 11.6% of emissions came from livestock feed, burps, and manure. (More recent estimates place this figure anywhere between 11.1% and 19.6%). This is a considerable environmental impact.

Though I am conscious of these negative impacts, I still eat eggs, dairy, chicken, beef, fish, shrimp, and the occasional lamb. I still partake because animal products are tangibly delicious and healthy; whereas my guilt and discontentment are abstract and diffuse. Repenting for these sins is difficult. Hopefully, through modern-day indulgences, my soul can be saved.

II. the concept of “offsetting”

(I think the word “offsetting” is somewhat silly, especially when applied to animal suffering. I don’t refer to donations to Against Malaria as “infecting children offsets.” However, for clarity, I refer to donations to animal welfare and environmental charities as offsets)

Imagine a prominent oil and factory farming CEO, Anders, who makes weekly private jet trips. Now, imagine that same CEO except they are vegan. In this case, the positive impact of Anders’ veganism is likely outweighed by his contributions to oil and factory farming. It is better than nothing, but it’s not enough. We (vegans and vegan-sympathizers) judge Anders as worse for the world than he is better because compared to the average person, he contributes to far more pollution and suffering.

Brute utilitarianism is especially applicable to the veganism rubric because veganism's contribution is an abstraction—diffuse, hard-to-quantify reductions in demand for animal products leading to diffuse, hard-to-quantify reductions in negative impacts.

To illustrate this further, consider that there is little meaningful distinction to draw between a steak A eaten on December 26th and a steak B eaten on February 8th. Furthermore, eating the steak is not necessarily the issue. If the steak was bought on February 8th, and thrown instantly into a landfill, the negative impact still stands, because demand is what matters. And, if someone has the choice between buying steak from a small farmer with free-range carbon-sequestering cattle herds, compared to caged, factory-farmed cattle (assuming an equal price and emissions profile), the better choice is unequivocally the free-range steak—because demand only matters insofar as it promotes negative impacts.

So, with no stark difference between steak a and b, between eating and buying, between buying and demand contribution, and between demand contribution and negative impacts—the only consequential variable is the net negative impact.

Therefore: if you had a magical button that reduced suffering and GHG emissions by three steak-equivalents, which could only be activated by eating one steak, pressing that button and eating the steak would be better than not pressing the button and remaining vegan.

But wait, you may respond. A doctor who saves ten lives and then murders ten random people is not morally neutral! Even if the net harm is all that matters, there is still something unacceptable about causing harm in one place, even after reducing it elsewhere. I agree. However, unlike this serial killer doctor, the direct harms caused by animal consumption are very unclear, especially relative to the direct benefits caused by offsetting.

III. Is Veganism Effective?

Note: I am uncertain about the following argument and I welcome your perspective on it:

One knock against veganism’s efficacy concerns the economics of meat markets. If I stop consuming animal products, the aggregate demand for animals decreases. When aggregate demand for a product decreases, supply and price also decrease. However, when the price drops—more people buy. This is especially true for meat products, which are highly elastic. Beef, in particular, is quite close to unitary elasticity (one percent change in price = one percent change in demand)

Overall, aggregate demand for meat has steadily increased year over year due to increased incomes and living conditions in developing countries. Even worse, if we assume that demand is being substituted for demand from poorer areas, the net effect is that the demand for lower-priced meat relative to higher-priced meat increases. Therefore, by refusing to purchase animal products, the supply of animal products does not appreciably decrease, however, hyper-efficient factory farms likely gain more market share.

This argument has been made before, and is responded to by McMullen & Halteman in “Against Inefficacy Objections: the Real Economic Impact of Individual Consumer Choices on Animal Agriculture” (2018). I think their counterargument is not incredibly persuasive. I encourage you to read the article itself, but here is a summary of their four responses;

There is a threshold effect—once the demand for animal products drops by a specific amount (usually a predetermined amount equal to the size of a shipment from a supplier to a distributor)—there is a concrete reduction in the overall supply.

The animal market is incredibly efficient and highly responsive to changes in prices and demand.

Farmers have low margins, and cannot continue to drop prices, so they must eventually reduce supply.

Because individual farmers have no price-setting power, prices are always determined by costs faced by the marginal producers. “This means that almost all of the price variability, over the long run, will be determined by production costs, not demand.”

The authors conclude by conceding that a decrease in price leading to an increase in demand from lower-income consumers “is a likely impact in the short run,” but that in the long run, supply will decrease.

However, while the marginal producer cannot cut costs, distributors (like grocery stores) can. The farming industry is consolidating over time precisely because factory farms are so much more efficient. I counter-counter-argue that the likeliest response by distributors is a further pivot toward the cheapest possible suppliers, not a reduction in the amount purchased.

Even conceding their points, this still means that the direct positive effect of veganism will not be realized until the far future, which further supports my initial stance on the validity of offsetting.

Importantly, veganism has other positive effects besides demand reduction. In social settings, one vegan can affect a group’s behaviour. For example, when my dear (vegan) friend, Theo (of Theo’s Take), comes over for dinner, we use tofu, instead of chicken or beef, as the main protein. Secondly, veganism drives up demand for alternatives like tofu and tempeh, helping build efficient and accessible markets. Thirdly, veganism is a status symbol which demonstrates a commitment to a belief; this commitment increases credibility when advocating for animal rights. Lastly, McMullen & Halteman describe a Supply Chain Effect—eating less meat means fewer animals needed for breeding, or in the case of fish, to create fish food. All of these adjacent effects multiply the positive impact of veganism.

Ultimately, the exact way that veganism impacts meat markets is unclear. In the long run, supply will likely decrease. However, in the short run, the markets may adjust—potentially in negative ways.

IV. The Magical Indulgence Button

Donating to charity is a highly effective way to promote good in the world. Intuitively, a good charity is almost always more effective in doing good than a well-meaning person. This is because a good charity is likely composed of experts who care deeply about a given issue. A good charity can pool resources, including money and political capital, unlocking economies of scope and scale. Large charities are accountable to donors, and watchdog groups. Large charities publish detailed, independently-audited reports compiling its operations and their effects each year. Lastly, by examining the previous successes of a charity, we can make reasonable predictions about their future impacts, cost efficacy, and more.

To offset the animal suffering and GHG emissions associated with eating meat, you can donate to good charities, which approximately offset your negative impact. These respective donations work similarly by funding projects promoting animal welfare or environmentalism, respectively.

Animal Suffering Offsetting

Many reputable animal welfare charities have made impressive strides towards reducing suffering. For example, the Humane League has lobbied the US, UK, and Mexican governments to implement fish and chicken farming regulations. In the US, this lobbying was successful—leading, in part, to Proposition 12, the strongest legislation for chicken welfare in the country. The Humane league also targets companies and individuals. One of their corporate outreach projects secured 25 cage-free commitments (with an estimated 48%–84% follow-through rate). These corporate campaigns are effective and improve 9-120 chicken life-years per dollar spent. On the higher end, estimates place cost efficacy at 501 to 846 quality-adjusted life years per dollar spent.

The Shrimp Welfare Project (SWP) is focused, aptly, on shrimp suffering. Similar to the Humane League, they primarily focus on corporate outreach. Shrimp, which are sentient creatures (at least according to the UK government) are farmed by the hundred billion. They do not have the same level of legal protection as other farmed animals. A common method of farming is to temperature shock the shrimp, leaving them to asphyxiate and freeze on ice. One of the SWP’s initiatives includes promoting electric stunner use, which, at the very least, facilitates a humane death.

These charities are at the front line of new legislation, corporate outreach, and research initiatives for animal welfare. They are worthy of donating to, offset or not.

Carbon Dioxide Offsetting

Carbon offsetting is a more controversial topic. The industry has been mired in scandal for manipulating GHG conversions, selling phantom or duplicate credits, and wildly overestimating the impact of their projects.

Rather than donating to specific charities, most offsets occur through third-party verifiers like “Gold Standard,” which aggregate, register, and audit emission-reducing projects. Through these brokers, you can donate to specific projects, leading to a positive, environmentally friendly impact.

One common project type uses donations to subsidize efficient cook stoves for rural communities in Global South countries. Often, these rural communities rely on open wood fires for cooking. These stoves reduce emissions induced by cooking, prevent deforestation, and increase air quality. However, these projects’ effects are overstated. Measuring the counterfactual world is difficult; and, many services use incredibly charitable (pun intended) assumptions to advertise their impacts. Preventing deforestation is wonderful, but many people use fallen, or already dead wood to cook with. Replacing open wood fires is fantastic, but many people simply use the clean cookstove in tandem with their woodstoves.

A Nature study of cookstove offset markets found that the benefits are overstated by 10 times on average. The study mentions that Gold Standard certified cookstoves were only 1.5 times over-credited because their projects are more rigorously measured.

This overstating problem follows for most carbon offsets. From my research, “deforestation prevention” projects appear to be especially unreliable. If you donate to carbon offsetting, make sure that the project is independently verified by a third party such as VCS, CDM, or Gold Standard.

Notably, carbon offsetting is much cheaper than promoting animal welfare. This may be because emissions reduction is relatively easy, with plenty of low-hanging fruit to focus on, whereas animal suffering is relatively entrenched and less of a mainstream issue.

V. Pressing the button

Farmkind is a wonderful charity that offers nifty resources, calculators, and visualizers for animal impacts. With their “compassion calculator,” I estimated that 24 chickens, 0.1 cows, 25 fish, and 71 shrimps were raised to produce my food in the last year. Using this study, this report, and liberal estimates of my dietary habits, I calculated that my diet cost the world 3.87 tonnes of CO₂ equivalents (which, is just under the average North American dietary contribution of 4.1 CO₂ equivalants).

In the past year, I have donated $305 Canadian dollars to the Humane League, which according to Farmkind, helped 177 chickens become cage-free. My $150 donation to Gold Standard for cookstoves in Zambia supposedly offsets 7 tonnes of CO₂ equivalents, but we can adjust downwards by 1.5 for a true offset of 4.67 tonnes.

VI: In conclusion

Veganism is good because animal suffering is terrible. Additionally, veganism avoids harm to the environment and promotes positive trickle-down effects. However, the impact of veganism is not immediate or direct—it is a drop of water in the pool of the farm industry, grocery stores, and other consumers. In the short term, the effects are unclear—potentially even null. In the long term, veganism likely reduces the overall supply of meat.

Similarly, offsetting has a positive long-term effect. Through animal welfare and environmental charities, people can donate money to promote concrete positive impacts. Though the impacts of these charities are often overstated, adjusting for the overstatement still leaves a relatively affordable path toward offsetting the harms of animal consumption. With my donation, I have likely made a more positive impact than I would have had I spent the past year as a vegan. At the very least, I have beaten a hypothetical-vegetarian Humam.

Is animal consumption worth 455 dollars per year to me? In some ways, yes. However, I feel hypocritical—this essay was a wake-up call to reduce my intake of meat and other animal products.

What do you think?

Leave your clucks, moos, and baaas in the comments down below.

Some issues with this essay:

Donating to these charities and being vegan is obviously the best choice. It is even worse to “offset” when I could have donated to other, more effective charities instead.

There are other significant environmental harms caused by eating meat—fertilizer, water, and land use, for example, that I did not account for in my calculations.

I am not specific enough about the type of suffering I caused through consumption, and the types of suffering reduced through offsetting.

I left so many interesting threads un-tugged. One question I have for a future essay is: Does eating free-range products increase animal welfare, or does it drive prices up for humane animal products, leaving consumers (who are highly elastic) to switch towards cheaper, higher-suffering animal products? Unfortunately, I spent a criminal amount of time researching dead ends for this post, and I need to draw a line somewhere, for my sanity.

very cool humam

you should def check out Glenn's article on how climate change is worse than factory farming https://statesofexception.substack.com/p/climate-change-is-worse-than-factory